On 1 November 1666, a young farmer named Abraham Morten took one final, agonizing breath. He was the last of 260 people to die of bubonic plague in the remote village of Eyam in Derbyshire. His fate had been sealed four months earlier when villagers decided to shut themselves off from the rest of the world: a sacrifice they made in order to save the lives of their neighbors in surrounding villages.

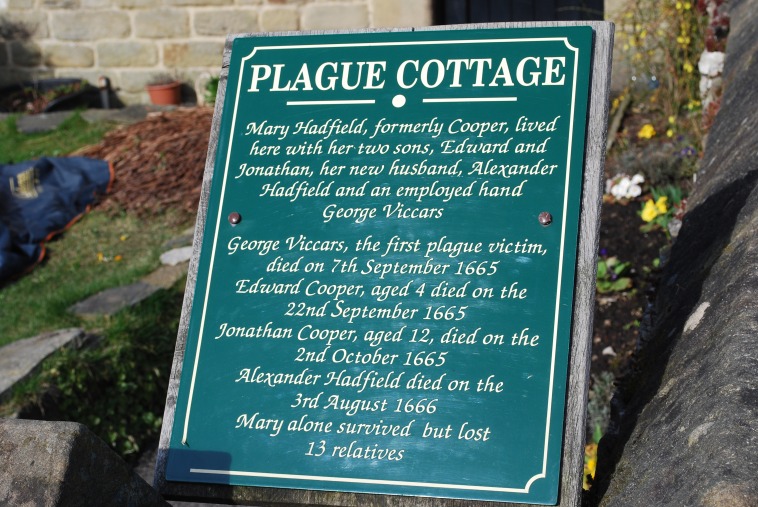

The nightmare began on an unremarkable day in September, 1665. George Viccars—a local tailor in Eyam—received a consignment of cloth from London for his shop. Upon inspection, Viccars noticed that the cloth was damp. He hung it before his fire to dry, not realizing that it was playing host to fleas that were carrying the bubonic plague.

Viccars was dead within a week.

The pestilence spread rapidly throughout the village. Panic broke out as villagers began making preparations to flee Eyam for contagion-free surroundings. It was then that two local clergymen, William Mompesson and Thomas Stanley, decided to intervene in order to stop the plague from spreading to neighboring villages. In a joint sermon, the two men pleaded with their fellow townspeople to recognize that it was their Christian duty to remain in Eyam until the scourge had played itself out, and to prevent the disease taking hold in other villages. Moved by the clergymen’s words, the villagers decided to make the ultimate sacrifice: they sealed themselves off from the rest of the world.

In order to do this, they created a stone boundary around Eyam. No one was allowed in, and no one was allowed out. People from surrounding communities brought food and clothing to the disease-ridden village. They would leave their goods on the stones and pick up their payment from a well filled with water and vinegar [pictured above], which would disinfect the coins.

Within Eyam’s self-imposed bounds, the plague was unrelenting, killing people arbitrarily over the next fourteen months. No one was untouched by tragedy, including Elizabeth Hancock, who inadvertently brought the disease back to her farm after helping to bury a fellow villager’s body. Within a week, all six of Elizabeth’s children, as well as her husband, had died. Not wanting to put anyone at further risk, Elizabeth took on the task of burying her entire family herself.

By August, two-thirds of Eyam’s population had died from the plague, including Mompesson’s own wife. The cemetery had become so full that the dead had to be buried in nearby gardens and fields. The dwindling congregation—which grew smaller daily—began holding services outside in an attempt to halt the rampant spread of the disease. There, in the open air, they prayed earnestly to be delivered from the suffering God had seen fit to thrust upon them.

By November, the plague had finally subsided. Of the village’s 350 original occupants, only 90 had survived. However, it is not the statistics that are noteworthy in this story, as these are fairly typical of plague mortality rates during this period. Rather, it is the villagers who are extraordinary. They stopped the spread of plague by their courageous, selfless actions, and in doing so, ensured that they would not become just another set of nameless statistics generated by that horrific epidemic.

By November, the plague had finally subsided. Of the village’s 350 original occupants, only 90 had survived. However, it is not the statistics that are noteworthy in this story, as these are fairly typical of plague mortality rates during this period. Rather, it is the villagers who are extraordinary. They stopped the spread of plague by their courageous, selfless actions, and in doing so, ensured that they would not become just another set of nameless statistics generated by that horrific epidemic.

No one in the surrounding area contracted plague during this time.

If you’re interested in learning more about the plague, check out Rebecca Rideal’s excellent book 1666: Plague, War and Hellfire.

And don’t forget you can now pre-order my book, The Butchering Art. All pre-orders count towards first-week sales once the book is released, and therefore give me a greater chance of securing a place on bestseller lists in October. I would be hugely grateful for your support. If you’re in the US, click HERE. If you’re in the UK, click HERE. Info on further foreign editions to come.